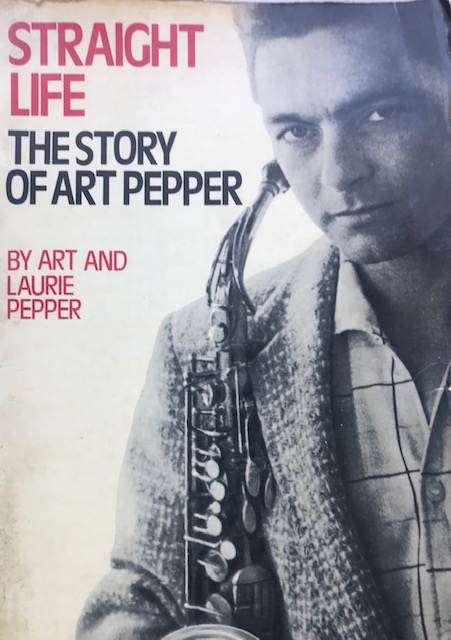

Why Art Pepper’s Straight Life Is Still the Most Harrowing Jazz Memoir Ever

(This article first appeared in the August 2019 issue of JazzTimes magazine.)

Early in his memoir, Straight Life, the late jazz legend Art Pepper relates a story about being in the U.S. Army during World War II, stationed in London. Once, on a day when he had some free time, he met a young woman on the street near Piccadilly Circus. They spent the day drinking Old Kuchenheimer beer and wandering the city, occasionally canoodling, kissing, and rubbing up against each other. As night fell, Art demanded sex. The woman resisted. So he dragged her into a dark cemetery and took it.

The word rape is not used, but it’s clear what occurred. The irony is that Pepper contracted a venereal disease from the encounter.

A few pages later in the book, after Pepper has returned to his hometown of Los Angeles, he describes a sexual compulsion so strong that he becomes a Peeping Tom, drilling holes in hotel room walls to spy on adjoining guests having sex, and prowling his neighborhood to peek into windows at women showering while he masturbates.

Straight Life was published in 1979. There’s a good chance that today, in the #MeToo era, the book would never have found a publisher. If it had, there’s a good chance that no nightclub would book Art Pepper, nor any record label sign him to a deal.

What made the book so shocking then is what makes it shocking now: unadulterated, raw truth-telling with no sugar coating and not much self-analysis. What you see is what you get.

The experience is greatly enhanced if you have knowledge of Pepper’s style of playing—his voice on the horn—which was one of sheer beauty. His tone was melodic, his phrasing often sensitive and gentle. The notes tumbled out of his alto saxophone with such warmth and feeling that it is almost impossible, while reading Straight Life, to reconcile the sublime nature of Pepper’s art with the dark, self-destructive tendencies that animate his memoir.

This tension between the artist and the man is what made the book so startling when it was first published, and today—reading the book for the third time—I still find it hard to reconcile. Art Pepper, who died in 1982, was a man of contradictions. He left behind a lifetime of beautiful music and a book so scalding in its sexual candor and emotional brutality that in today’s marketplace it would be too hot to handle.

Straight Life does not delve much into Pepper’s evolution as a musician. There is a sprinkling of anecdotes about recording sessions, and significant pages on his time as a young saxophonist with Stan Kenton’s orchestra. But this is mostly a book about the man’s psychosis: his years as a heroin addict, and his various stints in prison. On both of these accounts, the book stands as one of the most revelatory ever published. Gary Giddins, reviewing the book in The Village Voice back when it was published, called it “superior to Burroughs’ Junkie on that subject and Braly’s On the Yard on that one.”

Pepper was not the first musician to detail the unruly particulars of a narcotics habit or to test the boundaries of literary propriety. In Really the Blues, first published in 1946, Mezz Mezzrow describes acquiring an opium addiction in the 1920s; in Lady Sings the Blues, a memoir attributed to Billie Holiday and co-writer William Dufty, the singer cops to having a heroin addiction and describes the cruel ways that police and narcotics agents harassed her and sought to destroy her career; in Charles Mingus’ Beneath the Underdog, which, in some ways, was a precursor to Straight Life in its lowlife verisimilitude, the irascible bassist famously describes (in detail) having sex with 26 Mexican prostitutes in two-and-a-half hours at a cheap bordello in Tijuana.

All of these books, in a way, sought to break through the genteel formula of popular autobiography, in which publication to a mass audience requires creating an artificial distance between the writer (often a ghost writer) and the reader. Pepper, on the other hand, like a street-corner storyteller, drags the reader deep into his hellish descent with the kind of novelistic details you might expect from a writer like Hubert Selby, Jr. or Henry Miller. When Pepper is released from his many stints in prison, there is little doubt that he will return to the junkie life. Usually he is copping and using dope within days of his release. When it comes to his relentless compulsion for self-destruction, the possibility of redemption through artistic expression is a distant dream. At times, reading Straight Life is like reading the autopsy of a man who is already dead but doesn’t know it yet.

So what is it that drives this brilliant artist to debase himself and consistently undercut his illustrious career? Though he never comes right out and says it, it’s clear that Pepper’s bête noire is the reality of race in America. The book was constructed by Pepper in a series of interviews with Laurie Pepper, his wife and co-author, at a time when the Black Power movement was in full throttle. There are times in the book when Pepper cuts loose with statements of racial aggrievement that come off as whining, given what is now commonly referred to as the reality of “white privilege.”

Pepper became a professional musician at a time when segregation was still very much in place. His descriptions of having to use his whiteness to get around the Jim Crow laws—flagging down cabs for black musicians in the band, ordering and picking up food from establishments where blacks were not welcome—are sensitively rendered, with an acute awareness of the basic inhumanity at play. But these passages also raise the specter of what price is paid by the person who is called upon to play the “white savior” role. Black jazz musicians, in a way, became dependent on white musicians like Pepper to deal with the day-to-day mechanisms of life on the road in a racist country. It doesn’t take a genius to see how this might lay the groundwork for internal relationships within a band that are fraught with anger and resentment.

These emotions were kept buried in the 1940s and ’50s, but by the 1960s the racial dynamics of jazz, as with all of society, bubbled to the surface. Pepper describes one time playing at a club in Los Angeles with his own group. On a break between sets, a friend points out that Pepper’s own bandmates, who are black, are laughing at him behind his back. Pepper confronts his drummer:

We went out in front of the club and I said, “Man, what’s happening with you?” And he said, “Oh fuck you. You know what I think of you, you white motherfucker?” And he spit in the dirt and stepped in it. He said, “You can’t play. None of you white punks can play.” I said, “You lousy, stinking black motherfucker! Why the fuck do you work for me if you feel like that?” And he said, “Oh, we’re just taking advantage of you white punk motherfuckers.”… I was really hurt, you know; I wanted to cry, you know; I just couldn’t believe it—guys I’d given jobs to, and I find out they’re talking behind my back and, not only that, laughing behind my back when I’m playing in a club!

It would be too easy to say that the insecurity and self-loathing stirred up within Pepper during moments like this made him a junkie, but it sure didn’t help. Dope and alcohol became Pepper’s coping mechanism, and it nearly destroyed him, until he wound up at Synanon, a controversial rehab facility in Santa Monica, where he met Laurie, his future wife and co-memoirist, and began to get some perspective on his life.

In the end, Pepper cites as his great gift not the fact that he was one of the best alto saxophone players who ever lived; he cites his ability to endure all that he did, which ultimately made it possible to access his humanity through his art.

At the end of Straight Life, the author describes a moment of virtuosity on the bandstand so transcendent that it deserves to be preserved here in all its glory:

We played the head, the melody, and then [Sonny Stitt] took the first solo. He played, I don’t know, about forty choruses, he played for an hour maybe, did everything that could be done on a saxophone, everything you could play … Then he stopped. And he looked at me. Gave me one of those looks, “All right, suckah, your turn.” And it’s my job; it’s my gig. I was strung out. I was hooked. I was drunk. I was having a hassle with my wife, Diane, who threatened to kill herself in our hotel room next door. I had marks on my arm. I thought there were narcs in the club, and all of a sudden I realized that it was me. He’d done all those things, and now I had to put up or shut up or get off or forget it or quit or kill myself or do something.

I forgot everything, and everything came out. I played way over my head. I played completely different than he did. I searched and found my own way, and what I said reached the people. I played myself, and I knew I was right, and the people loved it, and they felt it. I blew and I blew, and when I finally finished I was shaking all over; my heart was pounding; I was soaked in sweat, and the people were screaming; the people were clapping, and I looked at Sonny, but I just kind of nodded, and he went, “All right.” And that was it. That’s what it’s all about.

Art Pepper was a great musician who paid a heavy price for his art. With Straight Life, he achieved something few musicians can claim: literary immortality.

(T.J. English is an author of eight non-fiction books. His last article for JazzTimes was a historical assessment of Jerry Gonzalez and the Fort Apache Band.)

hands down the greatest sax man ever…

LikeLike