Ask the average Caucasian on the street if U.S. law enforcement engages in torture of its citizens as a matter of policy and you are likely to get an emphatic ‘no’. Ask a Caucasian in Chicago and you may detect a slight hesitation, as the person could have a vague recollection of the police torture scandals that plagued the city for more than thirty years. Ask a black person in Chicago this same question and you are apt to get a knowing scowl.

The fact that Chicago’s recent legacy of police torture is not a national disgrace for all U.S. citizen is itself a national disgrace.

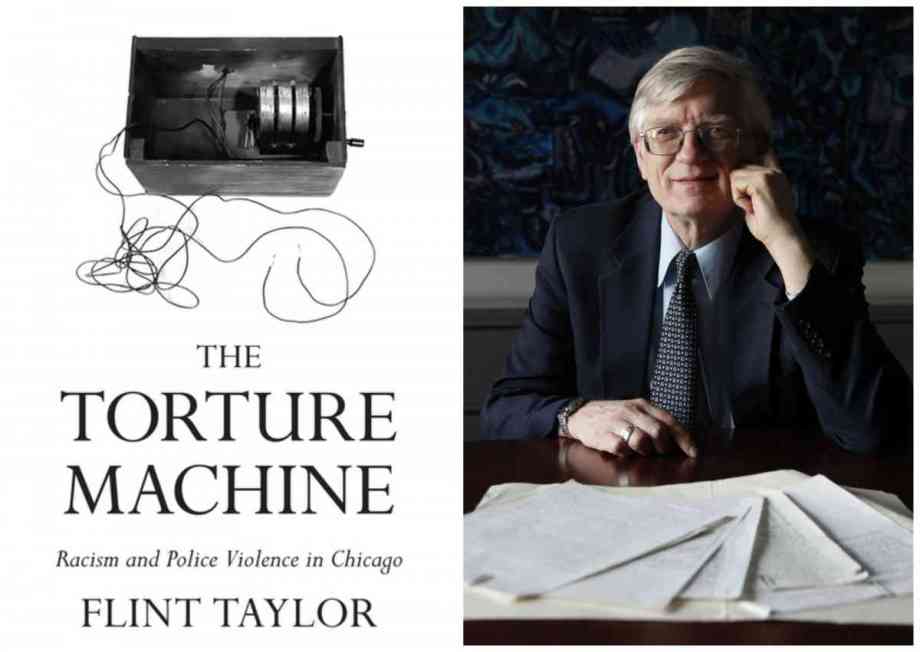

The Torture Machine, by civil and human rights lawyer Flint Taylor, seeks to enlighten the unenlightened. It is an exhaustive, harrowing account of the attempts to expose and bring justice to the most egregious example of police torture in the U.S. over the last century. And yet, since this important book was published by Haymarket Books earlier this year, there have been no major reviews in the U.S. media. Outside of Democracy Now, the progressive news analysis show on PBS, few, if any, major television networks or cable news outlet have had Flint Taylor on to talk about the book.

The Torture Machine is disturbing enough to turn your stomach. The majority of Americans seem incapable of absorbing or bending their collective mind around the full dimensions of this horror show. U.S. citizens – especially self-identifying white Americans – would rather that this recent history be buried away and forgotten.

In the city where these events took place, there has been a consortium of lawyers, activists, and a handful of journalists who stayed on the case. Taylor’s book is an attempt to fully document the efforts of these people, including his own efforts as a member of the People’s Law Office (PLO), the organization that spearheaded the long, excruciating fight for justice.

Here are the facts: Starting in the early 1970s, a cadre of detectives, primarily in a jurisdiction of the city known as Area 2, routinely used near-medieval forms of torture to secure false confessions from literally hundreds of suspects. The worst of the torturers, known as the Midnight Crew, were led by Jon Burge, a U.S. Army veteran who learned various torture techniques while stationed in Vietnam during the war. Burge’s primary technique was the use of a home-made black “shock box,” which was similar to the hand-crank telephones used by soldiers in Vietnam. Electrical wires extended from the box and were affixed by Burge and his crew to the ears, testicles, fingers, tongues, etc. of “suspects.” Cranking the device by hand sent an electrical shock through the wires that caused the suspects to scream, see stars, shake uncontrollably, pee or shit their pants, vomit, foam at the mouth, pass out, or, most pointedly, agree to sign a confession to virtually any crime the cops suggested, including murder.

The earliest known account of torture by Burge and his crew dates to 1972. This activity went on for years. It wasn’t until the early 1980s that Taylor, as a young civil rights attorney, came into the picture. Though only in his mid-thirties at the time, Taylor was no babe in the woods. Fourteen years earlier, as a law student, he had been involved in the investigation into the assassination of Black Panther Fred Hampton. It was in various legal proceedings stemming from that case that Taylor first became acquainted with the lengths to which “the system” would go to cover up the truth or protect a false narrative. Taylor was part of the team of activists and lawyers that eventually won a sizable settlement for the family of Fred Hampton, and in so doing exposed the fact that the official police version of Hampton’s death was a near-total fabrication.

The incident that brought Taylor and others from the PLO into the police torture case started with the murder of two Chicago police officers. In February 1982, Richard O’Brien and William Fahey were shot during a routine traffic stop on the South Side; they had just attended the funeral of a Chicago officer who had been shot dead only days before. Two black men were seen fleeing the scene in a brown Chevy. Mayor Jane Byrne and her police superintendent mandated the largest manhunt in the city’s history. The superintendent designated then-lieutenant Jon Burge, who headed the Violent Crimes Unit in Area 2, to lead the manhunt.

By then, it was known by people in the city’s criminal justice system – cops, medical personnel and prosecutors – that Burge was a racist cop who used torture to extract confessions. This may well have been why Burge was given the assignment to find the cop killers.

Burge and the Chicago PD unleashed a reign of terror on the South Side. Dozens of suspects were rounded up and brought to the Area 2 station house, where they were submitted to various techniques including but not limited to the black shock box. Another favorite technique was the “dry submarino,” where a plastic bag, hood, or synthetic typewriter cover was pulled tight over the head of a bound suspect until they were nearly asphyxiated. Other methods involved beating men on the bottoms or their feet and in the testicles with a rubber pipe, pressing their flesh against a steaming hot radiator, and placing the hands of suspects in a bolt cutter until they screamed for mercy.

These techniques were often accompanied by racial invective of the worst kind. All of the suspects were black, and the overwhelming majority of cops were white.

After a non-stop period of round ups, interrogations and torture (there would be upwards of two hundred complaints of police brutality filed with the Chicago PD by abused persons, ranging from mothers to a fireman and a taxi driver) Burge and his crew came up with two brothers they believed were involved in the cop killings. Andrew and Jackie Wilson were known criminals who fit the profile. It was up to Burge and his crew to extract the confessions. As Andrew Wilson later described it:

“They beat me up. They were kicking me around and slapping me on the floor. They grabbed a bag out of the garbage can, a gray garbage bag, and put it over my head. I was scuffling with them. I bit through it. They took it off of my head and one of them burned me on my arm. They slapped me back down on the floor but the big one, he kicked me, that’s how I got my eye messed up.”

Later, they administered electrical shock to Wilson’s gums, lips and genitals. Then they pressed his bare chest, thigh and face against the scalding hot radiator, leaving burn marks.

This angered Burge, who’d been out of the room during this last phase of the torture. Burge was a pro. He scolded the other detectives, telling them there would not have been any obvious marks on Wilson if he’d been the one administering the abuse.

Those burn marks on Wilson’s face did prove to be a problem. Not enough to stop him and his brother from being convicted for the murder of the police officers (even though they claimed the confession they signed was coerced), but the injuries that Wilson

sustained during his torture session led to a civil rights investigation undertaken by Flint Taylor and the PLO.

The Wilson case would be the beginning of a decades long journey deep into the dark and sinister world of police torture in the city. Partly, Taylor and the lawyers were spurred on by a series of anonymous letters they received from a source inside the police department. Dubbed “Deep Badge” by the lawyers (a nod to “Deep Throat” of Watergate fame), the source informed the lawyers that torture in Area 2 was way more widespread than anyone knew. “Burge hates black people and is an ego-maniac; he would do anything to further himself,” wrote the source. Deep Badge gave the lawyers specific names of victims, dates of torture sessions, and even suggested that the State’s Attorney’s office knew about the tortures and ignored or buried evidence.

Over the next decade, Taylor and his small team of lawyers hunted down and took depositions from dozens of black men they heard were victims of torture and coerced false confessions. For years, there had been talk in Chicago’s black community that this type of behavior was commonplace. Cops attached electric wires to the genitals of black men and beat them with clubs and phone books and smothered them with plastic bags. Some dismissed these stories as urban legend. But as lawyers and activists began amassing testimonials from the victims, the results were staggering. There were dozens – if not hundreds – of inmates who had vivid stories to tell of Jon Burge and his midnight crew.

In their efforts to expose barbaric and illegal practices from the recent past – and, also, to urgently call attention to the fact that these practices were still prevalent in Chicago even as the investigation was ongoing – Taylor and the lawyers encountered two major obstacles. One can best be characterized simply as “the Machine.”

It’s no accident that Flint Taylor titled his book The Torture Machine, which is a pointed reference to Burge’s black box but also to the famous Daley Machine (also known as the Cook County Machine) that ruled Chicago for decades. Urban political machines of the late-19th and 20th Century dominated a number of U.S. cities (in New York there was Tammany Hall), but none were more powerful than the political machine created by Richard J. Daley, who served as mayor and leader of the Cook County Democratic party for a quarter of a century.

Part of the Machine’s hegemony involved the degree to which it controlled all aspects of civic life. High ranking public officials, prosecutors, judges and on and on were hand-picked to serve by the Cook County Machine and were therefore beholden to it. “The system protects itself” is a truism in many facets of American life, but it has been especially true in Chicago, where virtually all public officials owed their careers to the Daley Machine.

Not the least of these officials was Richard M. “Richie” Daley, who at the time of the Wilson case was serving as State’s Attorney. As heir apparent to his father’s crown, and as the most powerful prosecutor in the state, it was Daley’s job to oversee any and all civil rights prosecutions. Let the record show that when it came to the worst police torture scandal in the city’s history, Richie Daley was negligent in his duties – perhaps criminally so. In the early 1980s, the future mayor of Chicago was presented with an internal police department memo sent by the city’s police superintendent. The memo detailed accusations of brutality, racism and torture — and identified Jon Burge by name. Specifically, the memo noted that the Cook County medical examiner was questioning the nature of Andrew Wilson’s injuries and alleging that he may have been subjected to cruel and unusual punishment. The medical examiner believed that an investigation was warranted. Daley did nothing to pursue these allegations. In fact, there is evidence that he deliberately buried the memo.

Daley wasn’t the only one. When Burge was brought in to oversee the manhunt for the killers of officers O’Brien and Fahey, Mayor Jane Byrne personally told the notorious racist cop to use any means necessary and not to worry about complaints to the department’s Office of Professional Standards (OPS).

As Deep Badge put it in his secret correspondence with the lawyers: “Mayor Byrne and State’s Attorney Daley were aware of the actions of the detectives… [They] ordered that the numerous complaints filed against the police as a result of this crime not be investigated.”

The culpability of the city’s two highest ranking public official in the scandal is eye opening, to say the least, but the more disturbing reality is the ways in which the conspiracy played out at the micro level. In dozens of legal hearings and trials, Taylor and the lawyers encountered bellicose judges and prosecutors – the Machine’s foot soldiers – who sought to undermine justice at nearly every turn. Judges made sure that depositions from torture victims and other evidence never saw the light of day in court. The justice system in Cook County was itself a significant part of conspiracy that made it nearly impossible to bring Burge or his co-conspirators to justice.

The other major obstacle was the people.

For the longest time, Taylor and the PLO had a hard time gaining traction with the media in Chicago and therefore were unable to harness a sense of outrage on the part of the populace. Partly, this was due to the perception that if, in fact, the police were torturing people, they were probably torturing known criminals, what our current U.S. President refers to as “bad hombres” who don’t deserve the protections of the U.S. constitution. The Wilson brothers, in particular, were found guilty of killing two cops. In the eyes of many, they deserved what they got. This mentality made it possible for Burge and other cops to continue using the black box and other means of violence even as they were being investigated for civil rights violations.

For the longest time, the story rarely made the front page of the newspapers or was given the status of being a lead item on the six o’clock news. There were activist groups such as the Coalition to End Police Brutality and Torture and the Center for Torture Victims and Families that marched in front of city hall and the federal courthouse, but their efforts largely fell on deaf ears. The conscience of the city lay dormant, with one notable exception.

John Conroy was a reporter for the Chicago Reader, an independent weekly newspaper. In early 1990, Conroy published a 12,000-word article that delved deep into the story. Entitled “House of Screams,” it was the first major piece of journalism to blow the lid off the scandal. Over the next two decades, Conroy wrote many pieces in the Reader. He tracked down John Burge’s Army buddies in Vietnam. He gave detailed first-hand accounts of torture that involved cops sticking shotguns in people’s mouths; loaded guns to their heads; cattle prods to the rectum and genitals; and the “savage torture” of young black men by white cops that sometimes focused on sexual debasement, a la the Abu Ghraib prison scandal yet to come.

“Among the many mysteries surrounding the torture cases,” Conroy wrote, “one question looms large. Where were the prosecutors? Could a torture ring exist for nearly two decades without anyone in the state’s attorney’s office noticing? Did state’s attorneys look the other way in Cook County? Did the office know – or have good reason to suspect – that torture was deployed under Jon Burge’s command?”

Conroy set the tone, and Taylor gives him full credit in The Torture Machine as the conscience of Chicago’s media during those years. Eventually, the rest of the city’s press did catch up and begin to acknowledge the immensity of the scandal, but that was years after Conroy had already amassed a body of work on the subject that should have won him a Pulitzer Prize. [Conroy later authored the book Unspeakable Acts, Ordinary People: The Dynamics of Torture, a brilliant exploration of the use of torture in Northern Ireland, the West Bank, and Chicago.)

In 1993, after an internal review, Burge was fired by the Chicago Police Department. But he continued to receive his pension and retired to a beach town near Tampa, Florida. It wasn’t until 2010 that Burge faced any real kind of justice. With local prosecutors in Cook County unable or unwilling to bring charges against Burge, the Feds stepped in and indicted the now notorious torturer on perjury and obstruction of justice charges. He was found guilty and sentenced to four and a half years in prison. He served his time and was released in October 2014. In September 2018, Burge died of natural causes at the age of seventy.

Burge was the most notorious police practitioner of torture in Chicago, but he was not alone. The practice was allowed to go on for so long that it inevitably spread to other jurisdictions. After Taylor and the PLO began to drag these cases into the light of day, they became harder and harder for the people to ignore. In 1999, Illinois state Governor George Ryan, a Republican who was not beholden to the Machine (though he was himself facing corruption charges that would eventually land him behind bars), instituted a moratorium on the use of the death penalty in the state and later, in 2003, he pardoned four inmates on death row and commuted 160 death sentences to life in prison, citing the fact that police practices in Chicago had hopelessly tainted hundreds of convictions.

Throughout the early 2000s, dozens more black men had their convictions thrown out and were released from prison after having served decades behind bars. The law suits were voluminous and threatened to bankrupt the city. A $7 million settlement in 2012 on behalf of two torture victims, and 2013 settlement of $12.3 million on behalf of two others, were just two of numerous cases that wound up costing the city an estimated $85 million.

In 2015, after pressure from civil rights organizations, the Chicago City Council established a reparations fund of $5.5 million for victims of torture, and Mayor Rahm Emanuel officially apologized to the citizens of Chicago for what took place in the city. As significant as these overtures may have been, they pale in comparison to the psychic and social devastation caused by this scandal over the course of nearly half a century.

In The Torture Machine, Taylor captures the mind-boggling nature of all this in forensic detail. It is not a light beach read. A lawyer by trade, not a polished author, the evidence is presented as if the book were a 500-page legal brief, but it is all-the-more powerful for it. There is little hyperbole or over-dramatization. The Torture Machine presents the legal case against those who perpetrated these crimes and allowed it to happen, and in so doing will stand as a potent literary testament on what is arguably the most sickening police scandal in the recent history of the United States.

________________

T.J. English is the author of eight non-fiction books, including The Corporation, Havana Nocturne and The Savage City.